FOURTH QUARTER ECONOMIC OUTLOOK – November 16, 2023

The Rolling Recession

by LESLIE CALHOUN, President and CEO and RYAN THOMASON, Portfolio Manager

In 2022, the prevailing sentiment among professional investors and their firms was that the U.S. was headed towards a recession due in large part to the Fed’s aggressive monetary policy. The focal point of discussion revolved around the nature of the economic downturn – whether it would be a soft or hard landing. Either way, the nearly unanimous consensus was that this recession would be the most anticipated recession in history.

In January 2023, the narrative took a decisive shift as the artificial intelligence (AI) theme claimed the spotlight. Swiftly, market pundits and professionals alike began advocating for a recession-free scenario, echoing the sentiments expressed by Fed Chair Jerome Powell. The rationale behind this optimism was rooted in the belief that AI would drive innovation, cut costs, and boost earnings growth. Concurrently, quarterly earnings of various companies surpassed initial estimates, propelling the market upwards.

As we approach the 4th quarter and reflect on the developments since the initial 0.25% rate hike in March 2022, it becomes evident that we’ve witnessed a rolling recession. A rolling recession occurs when economic downturns or recessions impact different sectors or regions of an economy at different times, resulting in a staggered pattern of economic contractions.

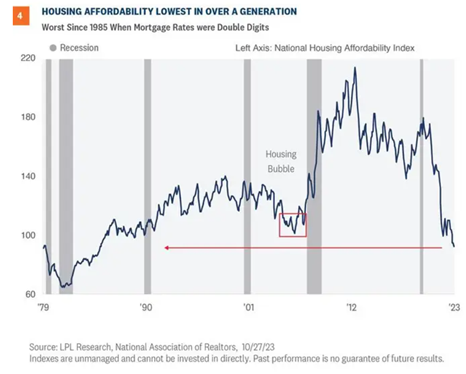

The initial contraction took place in the U.S. housing sector, triggered by a surge in mortgage rates that precipitated a substantial decline in aggregate demand, pushing affordability to an unprecedented low. At a certain point in 2022, existing home sales plummeted by nearly 40%. Presently, data suggests that the housing market is beginning to recover, with the Mortgage Bankers Association’s seasonally adjusted index reporting a 2.5% uptick in total mortgage application volume week over week (through November 8, 2023) and rates on 30-year mortgages declining from 7.86% to 7.61% (as of November 8, 2023). Furthermore, we have witnessed a notable 12.3% surge in new home sales in September 2023. While this is good news, we believe performance in U.S. housing will be fragmented across sub-markets. Unfortunately, the same positive outlook does not extend to the commercial real estate market, which is showing signs of continued stress as office properties continue to struggle to renew and renegotiate leases.

At the onset of lockdown restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a notable shift in consumer preferences towards products heavily reliant on semiconductors and chips. This shift resulted in a shortage, impacting various industries from automobiles to game consoles. In response, companies caught up by amassing inventories in anticipation of sustained trends. However, as demand forces began to decelerate in 2022, particularly for products like smartphones and laptops, semiconductor stocks witnessed a sharp decline. Layoffs at technology companies ensued and quickly spread to other sectors that were also seeing declining revenues. These revenue declines led to three consecutive quarterly earnings recessions for the S&P 500. This year, these industries have stabilized, and with renewed consumer demand and AI adoption, semiconductor stocks have experienced a resurgence that has pushed the market upward. With over 80% of the companies in the S&P 500 having reported earnings, it is evident that the earnings recession is now behind us.

In March 2023, the recession extended its impact to the banking sector, particularly affecting regional banks. A substantial influx of deposits flooded banks early in the pandemic as the government-initiated stimulus programs in response to COVID-19. Given the time required for banks to originate loans, they opted to significantly expand their securities portfolios to yield returns on those new deposits. This involved acquiring Treasury securities, mortgage-backed securities, and other interest rate-sensitive assets. However, the aggressive pace of rate hikes by the Federal Reserve caused a decline in bond prices, resulting in substantial losses on bank balance sheets. Moreover, it is noteworthy that small and regional banks hold a 26% share of commercial real estate loans. A significant portion of these loans is anticipated to mature over the next three years, potentially exacerbating the strain on the balance sheets of these smaller financial institutions.

Finally, we turn our attention to the consumer, who has yet to experience a recession or contraction. Historically, consumer spending has accounted for over 70% of the U.S. economy and has consistently been a key driver of growth. At present, the consumer balance sheet appears robust, reflecting years of deleveraging following the global financial crisis. Despite headlines highlighting elevated debt levels, the ratio of assets to liabilities are high for U.S. households. Moreover, debt servicing costs remain low compared to historical norms, even in the face of rising interest rates, and U.S. consumers’ financial obligations continue to be manageable relative to disposable income. Lastly, mortgage debt constitutes a substantial portion of total household debts, and many borrowers have been able to secure favorable mortgage rates in recent years. This strategic move has provided a significant shield for a considerable portion of debt against the impact of higher interest rates.

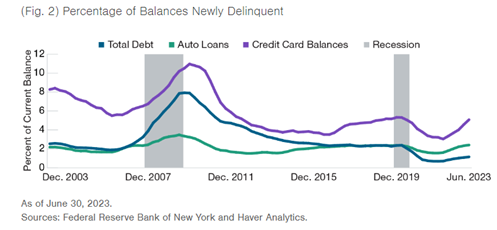

While the resilience of the U.S. consumer persists in this environment, there are growing concerns that warrant close observation. Notably, there has been a recent increase in delinquencies for credit cards and auto loans, especially among younger borrowers. Although overall delinquency rates remain below pre-pandemic levels, the uptick suggests that consumers may be experiencing the strain of escalating interest rates and the impact of high inflation on disposable incomes.

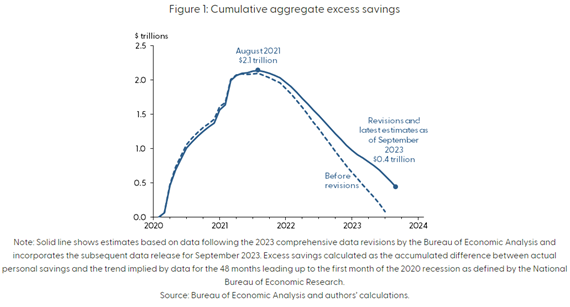

Another concern lies in the resumption of student loan debt payments for millions of borrowers. This will have a larger impact on younger borrowers, who are already exhibiting vulnerabilities through increased delinquencies on credit cards and auto loans. Additionally, the savings amassed during the peak of the pandemic across developed economies is gradually diminishing. While various estimates exist regarding the complete depletion of these excess savings, most analyses point towards Q4 2023 and into 2024. The absence of a savings buffer to shield consumers from the effects of rising prices, interest rates, or the resumption of student loan debt payments could potentially elevate pressure on the U.S. consumer.

If inflation attains the Fed’s 2% target and unemployment ticks slightly upward, this might prompt the Fed to gradually reduce rates. In this Goldilocks scenario, the consumer remains relatively unscathed, and we can assert that we have sidestepped a broad recession. Conversely, if the consumer weakens materially, entering their “rolling recession”, it will compel the Fed to lower rates albeit at a faster pace. The crucial question revolves around how much distress the U.S. consumer must endure for the Fed to act. The timing and the rate of change of the Fed’s rate cuts would determine the nature of the economic landing – soft versus hard. Nonetheless, as long as inflation trends in the right direction, we believe the Fed will act appropriately and promptly.

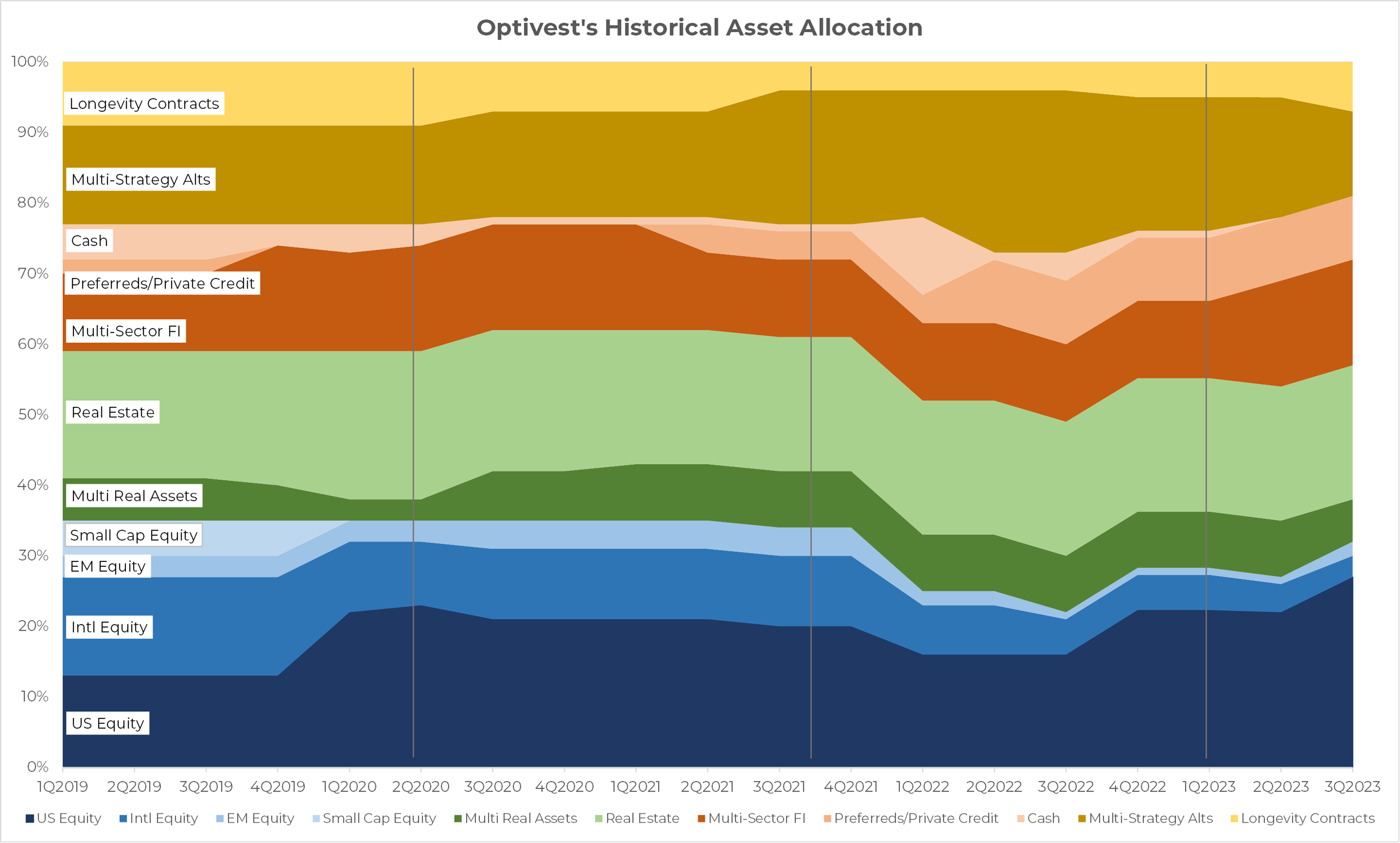

Depending on the outcome, we are likely to witness increased volatility and a range of returns across asset classes. The current portfolio is structured for a soft-landing scenario. However, a hard-landing scenario would necessitate an emphasis on quality and defensive investments. Recently, we have executed tactical rebalances between growth and value equities, extended the duration within fixed income while going up in quality, and have plans to allocate to senior bridge lending debt for real estate acquisition financing. Our portfolios are designed to endure various scenarios, and we are prepared to promptly make adjustments should conditions require.

Portfolio Returns in the Midst of Conflict

by MATT McMANUS, Wealth Advisor and COO

War and conflicts, whether local, regional or global, always bring with it a level of tension and raises anxiety in us as investors. It was first the Ukraine war and then geopolitical tensions between the US and China; later Afghanistan, and now the Israel-Palestinian situation. There has definitely been more than a fair share of geopolitical events in the past few years. Investors become anxious and markets become volatile because of the meaningful increase in the level of uncertainty.

An important part is to look to the history of financial markets to guide and teach us about how markets react under different circumstances. We all know that while history may not exactly repeat, it certainly rhymes. It is intuitive to think that wars and conflicts will have an outsized negative impact on financial markets. Normally, these events are seen as shocks to the system and hence the markets. However, the way markets react to these events may not be how most people would expect.

The bottom line is that many wars, both small and large, have had minimal impact on the underlying fundamentals or the existing trajectory of markets. However, for large wars with pervasive impact across broad regions, such as the Second World War, the financial markets fell in the period before the war but actually rose throughout the duration of the war.

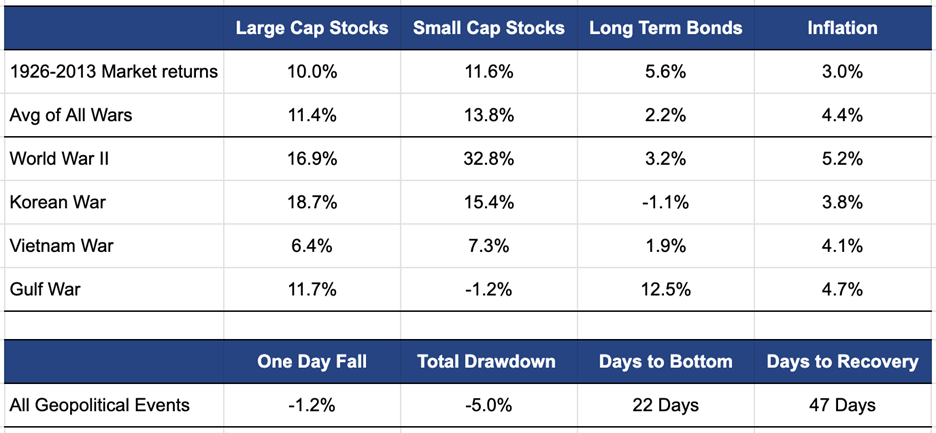

In fact, the long term study of 21 geopolitical events including terrorist acts and shock events that led to war since 1941 by LPL Research shows that typically across these 21 events that range from the Pearl Harbor attack to the many Middle Eastern conflicts to the 9/11 attacks, the market reacted on average by falling -1.2% in one day and around -5% to the bottom which normally took 22 days to reach that bottom from the day of the event but recovered that loss in 47 days on average.

How markets have reacted to wars and geopolitical events

Note: S&P 500 index for geopolitical events. Large cap and small cap indexes in the US market for the wars. Source: LPL Research, CFA Institute, Bloomberg, Endowus Research

Furthermore, a study by CFA Institute shows that across all major wars since 1926, stocks typically returned 11.4% for large cap stocks during wartime versus an average of 10% during the whole period and 13.8% for small cap stocks during wartime versus an average of 11.6% during the whole period for the overall market. It is interesting to also note that the periods during war had an average inflation of 4.4% versus the whole period average inflation of 3% from 1941 to present day.

Of course, all wars are different and markets react differently to it. However, even the recent examples of the Ukraine war led to a 7% fall in the S&P 500 index in the weeks that followed but recovered a month later to above where the markets were when the war began, and we have seen a similar trend in the recent Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Why uncertainty, not war, is the enemy of markets

The markets are a pricing mechanism that tries to reflect in real time all known information available to the public. This is why the market is seen as a leading indicator or a good real time sentiment gauge of underlying fundamentals of the economy or business.

It is also why the worst thing for the market is not war or geopolitics or even a recession, but the uncertainty that creates volatility. With every news about impending war and rising geopolitical risks, the market is uncertain about the future outlook. It is another form of risk so a rising period of uncertainty is a form of rising risk.

Normally, if that level of uncertainty rises due to war or an increased tension in geopolitics, it can lead to investors moving their money to traditionally safer assets such as gold and precious commodities or safer currencies or bonds. However, some of these traditional safe havens don’t look as safe as they used to.

US government bonds, once heralded as the place to be whenever there was conflict or crisis as a “risk free” asset, have fallen from grace. The ongoing fiscal situation with falling credit ratings, rise in supply of issuances, high cost of servicing that debt have all led to a sense that the US Treasuries is not the safe place most people thought they would be.

Currencies such as the Japanese Yen and the Swiss Franc seem to have problems of their own. Commodities also struggle with the weaker than expected global demand especially from traditionally heavy consuming economies such as China, where growth and demand remain anemic.

However, despite the lack of good alternatives the markets go through cycles and what seems to be a new reality can also suddenly change. We have just had the fastest pace of interest rate hikes in many decades. Despite all of the above concerns, because the market is an efficient pricing mechanism, we are likely to have priced in all these knowns in the current market valuations. What will drive interest rates and fixed income markets is likely to be things that we do not yet know.

From what we do know, other things being equal, yields are closer to the peak than ever before. As a result, bonds are giving investors enough yields now to be compensated for taking the additional risk of investing in the fixed income market, whether it is treasuries or credit, regardless of where interest rates are headed. If growth slows then the likelihood of rate cuts next year as currently predicted by both the markets and the Fed is likely to give a boost to fixed income returns.

The stock market normally prices in risks pretty quickly and then focuses back on the economic and business fundamentals of growth and earnings – the fundamentals of the markets – rather than the vagaries of geopolitical winds. Of course, in the current Middle East conflict, the uncertainty lies in whether there will be an escalation into a broader regional war that may have a longer lasting impact especially on oil and other commodities, which in turn, like the Ukraine war did, will have impact on the trend in inflation and therefore interest rate policy. These second order effects are what will be priced in over the next few weeks. Once it is priced in, then the market will reassess and move forward as it has always done.

What history teaches us is that equity markets do not suffer as we would expect during wars and conflict. In fact, it has a decent return in that environment as long as the war does not land on its own soil. While a higher for longer interest rate environment is not good for markets, any significant rise in tensions or conflict is likely to lead to a policy response tilted towards an easing monetary and positive fiscal response initially and that is not a bad thing for markets, especially with less safe haven investments available to investors.

Summary

We look forward to what 2024 holds for us knowing we are well diversified so that however long it takes to tame inflation, we can continue to receive income with lower downside participation. When the Fed does eventually see the opportunity, they will begin to drop interest rates and at that point, we think we will be exiting the last trough of the rolling recession.

Respectfully,

Leslie, Matt, Ryan & Ashlee