THIRD QUARTER INSIGHTS – August 29, 2024

PERCEPTIONS

by LESLIE CALHOUN, President and CEO and MATT McMANUS, M.A., CFP®, Wealth Advisor and COO

Despite the weak July labor market report, the U.S. economy on balance continues to prove resilient to higher interest rates. GDP in the second quarter of 2024 surprised to the upside, while real consumer spending growth has held steady and credit card delinquencies continue to rise. Meanwhile we see weakness in labor markets and wage growth so we have to assume savings levels must be about to reflect a drop in the months to come, meaning the consumer strength we’ve seen thus far will begin to fade. Unemployment remains low, but has been increasing at an accelerating rate, creating concern the Fed is behind the curve. An overall slowing is expected and what the Fed’s goal has been but we now need to see if they can achieve the soft landing or if we will have a bumpier hard landing.

The U.S. economy has made some headway on inflation and core PCE is now below the Fed’s June meeting projection for 2024. Rate market expectations have been volatile, seeming to live from CPI print to CPI print, though going forward, the Fed and markets will likely be more sensitive to labor market data. The market recently has been pricing anywhere from 50 to 125 basis points of cuts in 2024, but the more important message is that the market has been consistently pointing to an equilibrium federal funds rate of 3.0% or greater, which would anchor long-term Treasury yields in the mid-3% range even after the Fed has normalized its policy stance.

The forecast of an imminent recession has faded as we near what should be the first rate cut since the Fed pushed rates in the most aggressive manner in history to stall out inflation induced by supply chain interruptions and stimulus payments. We don’t see much risk to the economy that warrants aggressive rate cuts as much of the market is pricing in so we won’t be surprised if we see a small cut in September and then we remain there for a while until we see more cracks. And as a reminder, rate cuts do not assure an automatic market rally as interest rate cuts not only lower borrowing costs but also lower rates paid to savers and this tends to create some pullback across the board. So to be prepared for what seems to be a greater chance of disappoint to what the market has priced in, we’ve taken profits after mid-year and rebalanced portfolios to be more resilient yet in the face of increasing volatility and perhaps eventual disappointment.

Abroad, we are growing our exposure to Emerging Markets as we see opportunity there due to their steeply discounted prices and also as a currency hedge should the US Dollar weaken from recent highs. Europe continues to be lackluster while we watch their rate setting policies make minor adjustments and political strategies shift and become more tense. Countries are haggling over immigration and affordability and looking more inward to steer policy around these issues.

With any reduction in interest rates, real estate will turn back toward long-awaited health and opportunity. As rents have begun to decline, multi-family and new home starts have declined. We should begin to see transaction volume increase and with the housing shortage still meaningful, rents should stay stable.

New Changes to the inherited ira rules

by MATT McMANUS, Wealth Advisor and COO

In just the last three weeks, the IRS has finalized the Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) rules for Inherited IRAs that were first modified after the passage of the SECURE Act, which represented a major shift in retirement planning and estate management. The SECURE Act famously eliminated the Stretch IRA for most beneficiaries of IRAs and other retirement accounts.

Prior to the SECURE Act, beneficiaries of Inherited IRAs had the ability to stretch distributions over their life expectancies. This provision, known as the “stretch IRA,” allowed beneficiaries to minimize annual distributions and tax liabilities by extending the withdrawal period. For many, this strategy facilitated long-term tax-deferred growth of the retirement assets inherited.

The SECURE Act significantly altered this framework. It mandated that most non-spousal beneficiaries must now withdraw the entire balance of an Inherited IRA within 10 years of the account holder’s death. This rule effectively eliminates the option to stretch distributions over the beneficiary’s lifetime. The 10-year rule applies to adult children, siblings, and other non-spousal beneficiaries. This change aims to accelerate the distribution of retirement funds, thereby increasing taxable income and tax revenue in the near term.

Special Considerations for Spousal Beneficiaries and Exceptions

In addition, the SECURE Act provided some flexibility for spousal beneficiaries. A surviving spouse has the option to treat the inherited IRA as their own, thus continuing to benefit from tax-deferred growth and distributions based on their life expectancy. Alternatively, they can elect to take distributions over their own life expectancy, which may provide a more manageable tax impact compared to the 10-year rule applied to other beneficiaries.

Certain exceptions to the 10-year rule also exist. For example, minor children of the deceased, disabled individuals, and beneficiaries who are not more than 10 years younger than the decedent are exempt from the 10-year distribution requirement. Minor children can take distributions over their own life expectancy once they reach the age of majority, at which point the 10-year rule would then apply.

The New Change to the 10 Year Distribution Rule

Now in the last few weeks we finally have clarity regarding RMDs during the 10-year distribution window. The new regulations divide inherited IRAs into two groups.

The first group is IRAs whose original owners hadn’t yet reached the beginning age for taking RMDs. A beneficiary of such an IRA can distribute it under any schedule, provided it is fully distributed by the end of the 10 years. The beneficiary can distribute some each year, wait until the end of 10 years to distribute it all, distribute the entire IRA soon after inheriting, or in any other pattern.

The second group is IRAs whose original owners had reached the beginning age for RMDs. During years one through nine after inheriting, the beneficiaries must at least continue the RMDs under the same schedule the deceased owner was using. Essentially, the beneficiary takes an RMD each year based on the age the deceased owner would have been that year. The entire IRA must be distributed by the end of year 10. The beneficiaries in the second group can also fully distribute the IRA any time before year 10, which would eliminate future annual RMDs.

The 10-year rule applies to both traditional and Roth accounts. But original owners of Roth IRAs don’t have to take RMDs, so their beneficiaries don’t have to take RMDs during years one through nine. They only need to distribute the entire Roth IRA by the end of year 10.

Furthermore, before now the requirement to take RMDs in years one through nine was only in proposed regulations and the IRS suspended the requirement the last few years by saying any penalties for failing to take those RMDs in 2021-2024 would be waived. In the final regulations, the IRS said it wouldn’t make the annual RMD mandate retroactive. The annual RMDs for the second group now don’t have to begin until 2025. But the 10-year rule applies without modification. Most retirement accounts inherited after 2019 must be fully distributed within 10 years after being inherited.

Impact on Estate Planning

These changes necessitate a thorough reassessment of estate planning strategies. The new RMD rules require adjustments to retirement account management and inheritance planning. Estate planners must consider these new requirements when developing strategies for asset distribution and tax optimization. For those with substantial IRA balances, strategies such as Roth IRA conversions or changes in asset allocation might be necessary to manage the impact of accelerated distributions.

Conclusion

The recent changes to the RMD rules for Inherited IRAs, driven by the SECURE Act, represent a significant shift in retirement and estate planning. By implementing a 10-year distribution requirement for most non-spousal beneficiaries, the IRS aims to accelerate the taxation of inherited retirement assets. Both individuals planning their estates and beneficiaries need to navigate these changes carefully, employing strategic planning to manage tax implications and ensure financial stability.

The Yen carry trade unwind

by RYAN THOMASON, CFA, Portfolio Manager

The first week of August brought significant volatility to global markets after the Bank of Japan (BOJ) raised interest rates from a range of 0.0%-0.10% to a single rate of 0.25%. This rate hike caused Japan’s Nikkei 225 to drop 12% in a single day (August 5), marking one of the largest moves since the 1987 crash. However, the index largely stabilized, rebounding 10% the following day. Similar movements were observed in other markets, such as South Korea and the U.S. It seemed we were witnessing the start of a major correction, with markets falling, the VIX spiking, and investors flocking to Treasury bonds—the safest assets available. What drove this surge in volatility, particularly in the Japanese market?

In early July, as technology stocks were peaking, the Japanese yen began appreciating sharply. Between July 10 and August 5, the yen rose 14% against the U.S. dollar, causing assets funded by yen-denominated borrowings to decline in value. Several factors likely contributed to this yen rally. On July 31, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) surprised markets with a larger-than-expected rate hike and committed to further rate increases, along with faster-than-anticipated quantitative tightening (reducing the assets on their balance sheet acquired during over a decade of quantitative easing). Additionally, worsening U.S. economic data and disappointing headlines from some mega-cap tech companies weighed on the dollar and stocks overall.

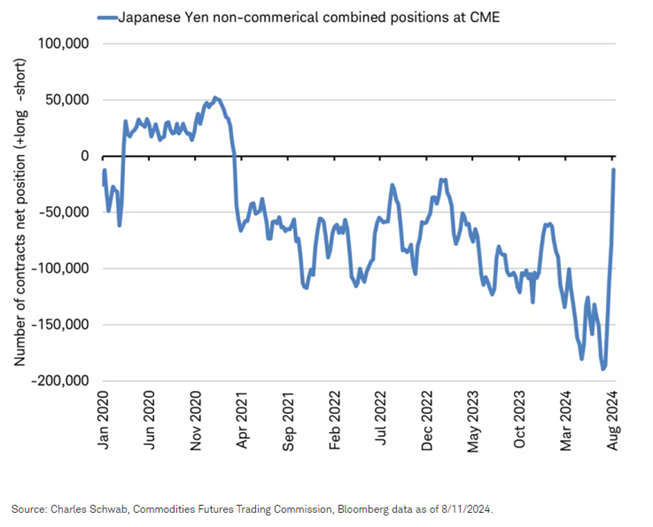

A popular carry trade involved going long (buying) technology stocks and shorting (borrowing) the yen. The yen has been the cheapest major funding currency due to its low-interest rates, making it an attractive option for borrowing. Given the consistent profitability of technology stocks, it’s easy to see why a significant portion of the short yen trade flowed into U.S. technology stocks. As traders processed the news from Japan and the U.S., many chose to unwind their positions. This meant selling the technology stocks they had purchased, converting the U.S. dollars back into yen, and repaying their yen debt. This unwinding happened swiftly and on a large scale, as evidenced by the number of short yen contracts, which dropped from 190,000 contracts (with a market value of $15.6 billion) on July 2 to nearly zero by August 6.

As the dust has settled over the past few weeks, the yen carry trade is regaining popularity. One of the main reasons for this resurgence is that BOJ Deputy Governor Shinichi Uchida has indicated that policymakers won’t rate rates further if financial markets remain unstable. However, this creates a conundrum: by making this statement, speculators are piling back into the trade, which could increase financial instability once again if the BOJ is forced to raise rates further to combat inflation. Another factor driving traders back into the carry trade is stronger-than-expected U.S. retail sales data, suggesting the Fed may not need to cut rates by 50 basis points at their next meeting in September. Futures markets as of August 20 suggest there is a 69% probability for a 25-basis point cut and a 31% probability for a 50-basis point cut (from 50% and 50% as of a week ago, respectively). The prospect of higher yields globally enhances the appeal of borrowing cheaply in yen, where interest rates are much lower, to invest in assets overseas.

While we believe that the unwinding of the yen carry trade is largely behind us, the BOJ finds itself in a precarious position. On one hand, they must address rising inflationary pressures that have been absent from the Japanese economy for years. On the other hand, keeping rates low helps maintain artificial market stability and allows Japan to continue issuing and servicing its debt, which exceeds 250% of GDP and consumes 22% of the annual budget. If rates increase, it could profoundly impact Japan’s ability to borrow, issue debt, and sustain economic growth.

Respectfully,

Leslie, Matt, Ryan & Ashlee